The tools used in traditional Chinese painting are paintbrush, ink, traditional paint and special paper or silk.

Chinese painting developed and was classified by theme into three genres: figures, landscapes, and birds-and-flowers.

The birds-and-flowers genre has its roots in the decorative patterns engraved on pottery and bronze ware by early artists. Among the common subjects in this genre, which reached its peak during the Song Dynasty (960 - 1279), are flowers, bamboo, birds, insects, and stones. The genre flourished under Emperor Huizong (1082 - 1135), who was an artist himself and excelled at both calligraphy and traditional painting, especially paintings of exquisite flowers and birds.

The birds-and-flowers genre has its roots in the decorative patterns engraved on pottery and bronze ware by early artists. Among the common subjects in this genre, which reached its peak during the Song Dynasty (960 - 1279), are flowers, bamboo, birds, insects, and stones. The genre flourished under Emperor Huizong (1082 - 1135), who was an artist himself and excelled at both calligraphy and traditional painting, especially paintings of exquisite flowers and birds.

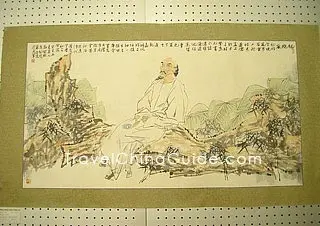

Painters who specialized in figures included images of immortals, emperors, court ladies, and common people in their works. Through their depictions of such scenes and activities as feasts, worship and street scenes, these artists reflected the appearance, expressions, ideals, and religious beliefs of the people. Chinese figure painting prominently features verve. The portrayal of figures saw its heyday during the Tang Dynasty (618 - 907). The master of painting, Wu Daozi (about 685 - 758), created many Buddhist murals and other landscape paintings that are marked by variety and vigor. One of his best known works is a depiction of the Heaven King holding his newborn son Sakyamuni to receive the worship of the immortals.

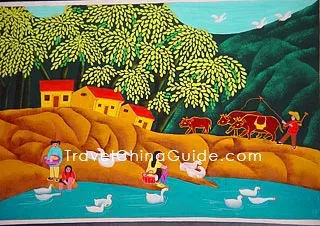

As far back as the Northern and Southern Dynasties (386 - 589), landscape painting separated from the figure genre and continued to enjoy popularity through the Tang Dynasty. This style reflected people's fondness for nature. The artist's use of ink and brush to paint a landscape changed, depending on the scenery itself, the weather (sunny or rainy day), the time of day (morning or night), and the season. The earliest known landscape painting was the Spring Outing by Zhan Ziqian of the Sui Dynasty (581 - 618). It shows an enchanting spring scene with people enjoying popular activities: gentlemen riding and ladies boating. A waterfall behind a bridge, near slopes and distant mountains are drawn with clear, fluent lines.

As far back as the Northern and Southern Dynasties (386 - 589), landscape painting separated from the figure genre and continued to enjoy popularity through the Tang Dynasty. This style reflected people's fondness for nature. The artist's use of ink and brush to paint a landscape changed, depending on the scenery itself, the weather (sunny or rainy day), the time of day (morning or night), and the season. The earliest known landscape painting was the Spring Outing by Zhan Ziqian of the Sui Dynasty (581 - 618). It shows an enchanting spring scene with people enjoying popular activities: gentlemen riding and ladies boating. A waterfall behind a bridge, near slopes and distant mountains are drawn with clear, fluent lines.

During the Ming (1368 - 1644) and Qing (1644 - 1911) Dynasties, innovation was stressed, and delicate seal marks, calligraphy, poems and frames increased the elegance and beauty of the paintings.

Much skill is required of the Chinese painter, who must wield the soft brush with strength and dexterity to create a wide variety of lines--thick, thin, dense, light, long, short, dry, wet, etc. Depending on his skills, he might specialize in detailed and delicate line drawing (Gongbi) or abstract, impressionistic (Xieyi) paintings. Line drawing is the basic training of a painter, who must learn it well before moving on to the delicate details of realistic scenes or the more abstract spirit of impressionism. Another special skill worthy of mention is painting with fingers instead of a brush, which creates a very different effect.

Much skill is required of the Chinese painter, who must wield the soft brush with strength and dexterity to create a wide variety of lines--thick, thin, dense, light, long, short, dry, wet, etc. Depending on his skills, he might specialize in detailed and delicate line drawing (Gongbi) or abstract, impressionistic (Xieyi) paintings. Line drawing is the basic training of a painter, who must learn it well before moving on to the delicate details of realistic scenes or the more abstract spirit of impressionism. Another special skill worthy of mention is painting with fingers instead of a brush, which creates a very different effect.

No matter what the subject or the style, traditional Chinese painting should be infused with imagination and soul. A traditional story that captures the Chinese view of painting tells about the establishment of a royal college of painting during the reign of Emperor Huizong. Examinations were held to recruit the best painters. Examinees were asked to draw a picture that reflected the joy of people who had just returned from a spring outing, an outing that had been so pleasant that even the horseshoes seemed fragrant. Many endeavored to depict this bright scene but only one work was chosen; the painter simply drew a horse's hoof followed by butterflies which were in graceful flight. This painter had managed to capture the essential spirit and beauty of the scene.

No matter what the subject or the style, traditional Chinese painting should be infused with imagination and soul. A traditional story that captures the Chinese view of painting tells about the establishment of a royal college of painting during the reign of Emperor Huizong. Examinations were held to recruit the best painters. Examinees were asked to draw a picture that reflected the joy of people who had just returned from a spring outing, an outing that had been so pleasant that even the horseshoes seemed fragrant. Many endeavored to depict this bright scene but only one work was chosen; the painter simply drew a horse's hoof followed by butterflies which were in graceful flight. This painter had managed to capture the essential spirit and beauty of the scene.

Нема коментара:

Постави коментар