Development of Chinese Embroidery

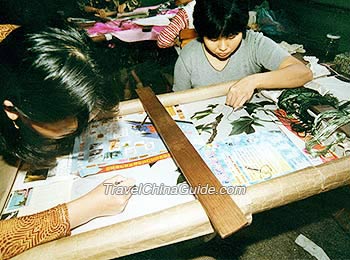

Embroidery is a brilliant pearl in Chinese art. From the magnificent Dragon Robe worn by Emperors to the popular embroidery seen in today's fashions, embroidery adds so much pleasure to our life and our culture.

The oldest embroidered product in China on record dates from the Shang Dynasty. Embroidery in this period symbolized social status. It was not until later on, as the national economy developed, that embroidery entered the lives of the common people.

Through progress over Zhou Dynasty, the Han Dynasty witnessed a leap in embroidery in both technique and art style. Court embroidery was set and specialization came into being. The patterns of embroidery covered a larger range, from sun, moon, stars, mountains, dragons, and phoenix to tiger, flower and grass, clouds and geometric patterns. Auspicious words were also fashionable. Both historic records and products of the time proved this. According to the records, all the women in the capital of Qi (today's Linzi, Shandong) were able to embroider, even the stupid were adept at it! They saw and practiced it everyday so naturally they became good at it. The royal family and aristocrats had everything covered with embroidery-even their rooms were decorated with so much embroidery that the walls could not be seen! Embroidery flooded their homes, from mattresses to beddings, from clothes worn in life time to burial articles.

The authentic embroideries found in Mawangdui Han Tomb are best evidence of this unprecedented proliferation of embroidery. Meanwhile, unearthed embroideries from Mogao Caves in Dunhuang , the Astana-Karakhoja Ancient Tombs in Turpan and northern Inner Mongolia further strengthen this observation.

During the following Three Kingdoms Period, one notable figure in the development of embroidery was the wife of Sun Quan, King of Wu. She was also the first female painter recorded in Chinese painting history. She was good at calligraphy, painting and embroidery. Sun Quan wanted a map of China and she drew one for him and even presented him embroidered map of China. She was reputed as the Master of Weaving, Needle and Silk. Portraits also appeared on embroidery during this time.

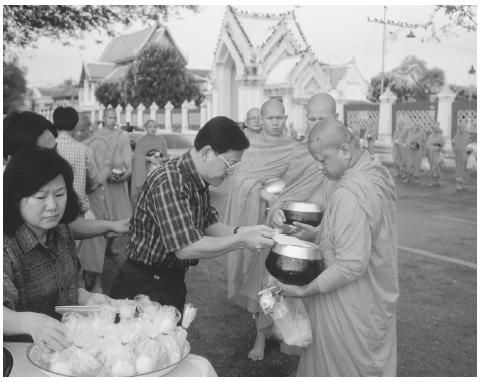

As Buddhism boomed in China during the Wei, Jin, Sui and Tang Dynasties, embroidery was widely used to show honor to Buddha statues. Lu Meiniang, a court maiden in the Tang Dynasty, embroidered seven chapters of Buddhist sutra on a tiny piece of silk! New skill in stitching emerged during this period.

Besides Buddhist figures, the subjects of Chinese painting such as mountains, waters, flowers, birds, pavilions and people all became themes of embroidery, making it into a unique art.

The Song Dynasty saw a peak of development of embroidery in both quantity and quality. Embroidery developed into an art by combining calligraphy and painting. New tools and skills were invented. The Wenxiu Department was in charge of embroidery in the Song court. During the reign of Emperor Hui Zong, they divided embroidery into four categories: mountains and waters, pavilions, people, and flower and birds. During this period, the art of embroidery came to its zenith and reputed workers popped up. Even intellects joined this activity, and embroidery was divided into two functions: art for daily use and art for art's sake.

The religious touch of embroidery was strengthened by the rulers of Yuan Dynasty who believed in Lamaism. Embroidery was much more applied in Buddha statues, sutras and prayer flags. One product of this time is kept in Potala Palace.

As the sprout of capitalism emerged in Ming Dynasty, Chinese society saw a substantial flourish in many industries. Embroidery showed new features, too. Traditional auspicious patterns were widely used to symbolize popular themes: Mandarin ducks for love; pomegranates for fertility; pines, bamboos and plums for integrity; peonies for riches and honor; and cranes for longevity. The famous Gu Embroidery is typical of this time.

The Qing Dynasty inherited the features of the Ming Dynasty and absorbed new ingredients from Japanese embroidery and even Western art. New materials such as gilded cobber and silvery threads emerged. According to The Dream of the Red Chamber, a popular Chinese novel set during the Qing Dynasty, peacock feathers were also used. Notably, the first book on embroidery technique theory was dictated by Shen Shou and recorded by Zhang Jian.

The first book of Chinese embroidery technique was dictated by an accomplished embroiderer, Shen Shou and recorded by Zhang Jian. Shen's original name was Xue Jun with Xue Huan as her alias. Shou was bestowed by Empress Dowager Cixi when she presented the Empress with the embroidered tapestry, Eight Immortals Celebrating Birthday. In 1911 she presented an embroidered portrait to the Italian Empress as a national gift. In 1915 her embroidery of the portrait of Jesus won the first award at the Panama Expo. Shen excelled in embroidery and devoted herself to teaching and training.

Zhang Jian was an outstanding industrialist in modern Chinese history. He set up one of the earliest textile factories, the first normal school, the first textile school and the first museum. He was passionate in art and culture; therefore, when he knew about Shen, he decided that her master skill must be preserved. Since Shen suffered from poor health and spent most her time in bed, Zhang volunteered to record every word. Thus, the cooperation between an old man of 60 and a lady in her 40s led to the birth of Xue Huan Xiu Pu (Embroidery Book by Xue Huan) in 1918. This anecdote should be very beautiful, especially in China, few men would humble themselves to act as a secretary for women. Because of their dedication, the world has valuable data about Chinese embroidery.

The Chinese word for embroidery is xiu, a picture or embroidery of five colors. It implies beautiful and magnificent. For example, the Chinese name for 'Splendid China' in Shenzhen, Guangdong was Jin Xiu Zhonghua. 'Jin' is brocade; 'Xiu' is embroidery; 'Zhonghua' is China. 'Xiu' is also a part of phrases such as xiu lou (embroidery building) and xiu qiu (embroidered ball). Embroidery was an elegant task for fair ladies who were forbidden to go out of their home. Embroidery was a good pastime to which they might devote their intelligence and passion. Imagine a beautiful young lady embroidering a dainty pouch. Stitch by stitch, she embroiders a pair of love birds for her lover. It's a cold winter day and the room is filled with the aroma of incense. What a touching and beautiful picture!

Major Styles of Chinese Embroidery

Chinese embroidery has four major traditional styles: Su, Shu, Xiang, and Yue.

Su Embroidery

Su is the short name for Suzhou. A typical southern water town, Suzhou and everything from it reflects tranquility, refinement, and elegance. So does Su Embroidery. Embroidery with fish on one side and kitty on the other side is a representative of this style.

Favored with the advantaged climate, Suzhou with its surrounding areas is suitable for raising silk and planting mulberry trees. As early as the Song Dynasty, Su Embroidery was already well known for its elegance and vividness. In the Ming Dynasty, influenced by the Wu School of painting, Su Embroidery began to rival painting and calligraphy in its artistry.

The above mentioned wife of Sun Quan, King of Wu of the Three Kingdoms and Shen Shou of Qing Dynasty were both embroidery masters from this area.

In history, Su Embroidery dominated the royal wardrobe and walls. Even today, Su Embroidery occupies a large share of the embroidery market in China as well as in the world.

Shu Embroidery

Originated from Shu, the short name for Sichuan , Shu Embroidery, influenced by its geographic environment and local customs, is characterized by a refined and brisk style. The earliest record of Shu Embroidery was during the Western Han Dynasty. At that time, embroidery was a luxury enjoyed only by the royal family and was strictly controlled by the government. During the Han Dynasty and the Three Kingdoms, Shu Embroidery and Shu Brocade were exchanged for horses and used to settle debts.

Originated from Shu, the short name for Sichuan , Shu Embroidery, influenced by its geographic environment and local customs, is characterized by a refined and brisk style. The earliest record of Shu Embroidery was during the Western Han Dynasty. At that time, embroidery was a luxury enjoyed only by the royal family and was strictly controlled by the government. During the Han Dynasty and the Three Kingdoms, Shu Embroidery and Shu Brocade were exchanged for horses and used to settle debts.

In the Qing Dynasty, Shu Embroidery entered the market and an industry was formed. Workshops and governmental bureaus were fully devoted to Shu Embroidery, promoting the development of the industry. Shu Embroidery became more elegant and covered a wider range. From the paintings by masters, to patterns by designers, to landscape, flowers and birds, dragons and phoenix, tiles and ancient coins, it seemed all could be the topic of embroidery. Folk stories like the Eight Immortals Crossing the Sea, Kylin presenting a Son and other auspicious patterns such as magpie on plum and mandarin ducks playing on the water were also favorite topics. Patterns with strong local features were very popular among foreigners at that time. These local features included lotus and carp, bamboo forest and pandas. Some bought embroidered skirts and used them as curtains!

Xiang Embroidery

Xiang Embroidery, an art from Hunan, was a witness of the ancient Xiang (Hunan) and Chu (Hubei) culture. Xiang Embroidery was a gift to the royal family during the Spring and Autumn Period. The most persuasive evidence of Xiang Embroidery is the articles unearthed in Mawangdui Han Tomb.

Developing over two thousands years, Xiang Embroidery became a special branch of the local art. Xiang Embroidery gained popularity day by day. Besides the common topics seen in other styles of embroidery, Xiang Embroidery absorbed elements from calligraphy, painting and inscription.

The uniqueness of Xiang Embroidery is that it is patterned after a painting draft, but is not limited by it. Perhaps because of this technique, in Xiang Embroidery, a flower seems to send off fragrance, a bird seems to sing, a tiger seems to run, and a person seems to breathe.

Yue Embroidery

Yue Embroidery, which encompasses Guangzhou Embroidery and Chaozhou Embroidery, has the same origin as Li Brocade. People generally agree that Yue Embroidery started from Tang Dynasty since Lu Meiniang, who embroidered seven chapters of Buddhist sutra, was from Guangdong. Portrait and flowers and birds are the most popular themes of Yue Embroidery as the subtropical climate favors the area with abundant these plants that are rarely seen in central China. In addition, Yue Embroidery uses rich colors for strong contrast and a magnificent and bustling effect.

Since Cantonese take to fortunes in an almost superstitious attitude, attaching a lucky implication to everything, red and green, and auspicious patterns are widely used. The most famous piece of Yue style embroidery is hundreds of Birds Worshiping Phoenix. Fish, lobsters, bergamots and lychee are also common patterns.

Others

Gu Embroidery distinguishes itself from other local styles by the fact it originated from Gu Mingshi's family during the Ming Dynasty in Shanghai , instead of from a certain place. Gu Embroidery is also known as Lu Xiang Yuan Embroidery. Lu Xiang Yuan, Dew Fragrance Garden in Chinese, was where the Gu Family lived. From the start, Gu Embroidery was different from other styles as it specialized in painting and calligraphy. The inventor of Gu Embroidery was a concubine of Gu Mingshi's first son, Gu Huihai. Later, Han Ximeng, the wife of the second grandson of Gu Mingshi developed the skill and was reputed as "Saint Needle". Some of her masterpieces are kept in the Forbidden City.Today Gu Embroidery has become a special local product in Shanghai.

Styles Facing Extinction

Bian Embroidery was regarded as a National Treasure during the Northern Song Dynasty. Bian refers to the capital of the Northern Song Dynasty, Bianliang, today's Kaifeng. Bian Embroidery was mainly used by the royal family so it was also known as Court Embroidery or Official Embroidery. The style was exquisite, precise and elegant to match the demeanor of the royal family. However, with the collapse of the dynasty, Bian Embroidery collapsed, too.

Han Embroidery originated from Chu (Hubei Province) and flew to Wuhan from Jingzhou and Shashi. Tinted by the Chu Culture, Han Embroidery is characterized by a rich and gaudy color with bold patterns and exaggerated techniques. Han Embroidery came to its heyday in the middle and later Qing Dynasty and obtained golden medals in international expos and competitions. Embroidery Street was formed in Daxing Road, Hankou, with nearly 40 workshops engaged in it. Bombing by the American planes of a Japanese magazine nearby destroyed the street as weavers fled.

Embroidery by Ethnic Groups

Among ethnic groups, Bai , Bouyei and Miao people are also adept at embroidery. Their embroidery uses sharp contrast of color and primitive design to express a mysterious flavor while embroidered Thangka by Tibetans shows their passion in religion.

"A silkworm spins all its silk till its death and a candle won't stop its tears until it is fully burnt." This Tang poem accurately describes the property of the silkworm. Despite technological development, a silkworm can only produce a certain amount of silk---1000 meters (3280feet) in its lifespan of 28 days. The rarity of the raw material is the deciding factor of both the value and the mystery of silk.

"A silkworm spins all its silk till its death and a candle won't stop its tears until it is fully burnt." This Tang poem accurately describes the property of the silkworm. Despite technological development, a silkworm can only produce a certain amount of silk---1000 meters (3280feet) in its lifespan of 28 days. The rarity of the raw material is the deciding factor of both the value and the mystery of silk.

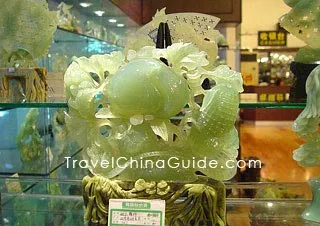

Jade has a history in China of at least four thousands years. Unknown to some, jade is found contained within the development of religion and civilization, having moved from the use of decoration on to the others such as the rites of worship and burial. Although other materials like gold, silver and bronze were also used, none of these have ever exceeded the spiritual position that jade has acquired in peoples' minds - it is associated with merit, morality, grace and dignity. In the funeral objects of the people of the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC - 24 AD), for example, we can see only high officials were buried with jade articles.

Jade has a history in China of at least four thousands years. Unknown to some, jade is found contained within the development of religion and civilization, having moved from the use of decoration on to the others such as the rites of worship and burial. Although other materials like gold, silver and bronze were also used, none of these have ever exceeded the spiritual position that jade has acquired in peoples' minds - it is associated with merit, morality, grace and dignity. In the funeral objects of the people of the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC - 24 AD), for example, we can see only high officials were buried with jade articles. As early as the 16th century, Jadeite was believed to be a precious and hard jade with healing qualities for the human stomach and kidneys. Since it was brought into China during the early Qing Dynasty (1644 - 1911), it had been doted on greatly. Jadeite contains an iron component which appears red, chromium that appears green, and many other colored types. Known as the 'king of jade', it is usually a more expensive type of jade.

As early as the 16th century, Jadeite was believed to be a precious and hard jade with healing qualities for the human stomach and kidneys. Since it was brought into China during the early Qing Dynasty (1644 - 1911), it had been doted on greatly. Jadeite contains an iron component which appears red, chromium that appears green, and many other colored types. Known as the 'king of jade', it is usually a more expensive type of jade. Lantian jade is produced in Lantian County, north of Xian in Shaanxi Province. It was also among the most charming ancient jades, for its rigidity made it easier to be carved into decorations and jewelry by our ancestors. The hue is uneven in colors of yellow or light green.

Lantian jade is produced in Lantian County, north of Xian in Shaanxi Province. It was also among the most charming ancient jades, for its rigidity made it easier to be carved into decorations and jewelry by our ancestors. The hue is uneven in colors of yellow or light green. To obtain a real and choice jade article, you should take pains to learn and appreciate it. The criteria lie in the brightness of color and luster, compactness of inner structure, and the delicacy of the craftwork. For example, nephrite creates an oily luster and jadeite creates a vitreous luster. Tiny cracks can lower the value of jade; on real jade, air bubbles cannot be seen; the more lenitive the higher quality of jade, and so on.

To obtain a real and choice jade article, you should take pains to learn and appreciate it. The criteria lie in the brightness of color and luster, compactness of inner structure, and the delicacy of the craftwork. For example, nephrite creates an oily luster and jadeite creates a vitreous luster. Tiny cracks can lower the value of jade; on real jade, air bubbles cannot be seen; the more lenitive the higher quality of jade, and so on. Embroidery is a brilliant pearl in Chinese art. From the magnificent Dragon Robe worn by Emperors to the popular embroidery seen in today's fashions, embroidery adds so much pleasure to our life and our culture.

Embroidery is a brilliant pearl in Chinese art. From the magnificent Dragon Robe worn by Emperors to the popular embroidery seen in today's fashions, embroidery adds so much pleasure to our life and our culture.  Originated from Shu, the short name for Sichuan , Shu Embroidery, influenced by its geographic environment and local customs, is characterized by a refined and brisk style. The earliest record of Shu Embroidery was during the Western Han Dynasty. At that time, embroidery was a luxury enjoyed only by the royal family and was strictly controlled by the government. During the Han Dynasty and the Three Kingdoms, Shu Embroidery and Shu Brocade were exchanged for horses and used to settle debts.

Originated from Shu, the short name for Sichuan , Shu Embroidery, influenced by its geographic environment and local customs, is characterized by a refined and brisk style. The earliest record of Shu Embroidery was during the Western Han Dynasty. At that time, embroidery was a luxury enjoyed only by the royal family and was strictly controlled by the government. During the Han Dynasty and the Three Kingdoms, Shu Embroidery and Shu Brocade were exchanged for horses and used to settle debts.